Dead whales tell tales

Have you ever come across someone cutting up a dead whale or dolphin and wondered 'what on earth are they doing?' BELOW We discuss the importance of learning from the dead and who you should report any PERISHED MARINE CREATURES to if you come across them.

WARNING: This blog contains graphic images.

Seeing a dead whale, dolphin, porpoise or even seal washed up on the beach can be very upsetting. These beautiful, powerful and charismatic animals bring so much joy and awe to people when they see them in our oceans, that the thought that they have ended up a mass of blubber and bone on our beaches seems a sad end.

But the world of whales and dolphins is still a mystery to us. Although we can learn a lot from living creatures - through surveys and sightings, recording their location and behaviour - there is much we can learn about their lives when they wash ashore dead.

Although an unpleasant sight (and smell) when an individual washes up, there is a group of trained volunteers whose interest is piqued, providing an opportunity to dig a bit deeper into the background of the animal and learn so much more about its life and ultimately it’s death.

The team ready for a day of learning

The team here at the Hebridean Whale and Dolphin Trust love watching these wondrous animals in their natural habitat, being inspired and empowered to continue our work to learn more, so we can better protect them. Understanding species - at both an individual and population level - is crucial to this outcome. So, back in July, we took a trip to the Scottish Association of Marine Science (SAMS) in Oban, where we met the dedicated team from the Scottish Marine Animal Stranding Scheme (SMASS) to be trained in gathering data, so we can become part of their Scotland-wide volunteer network.

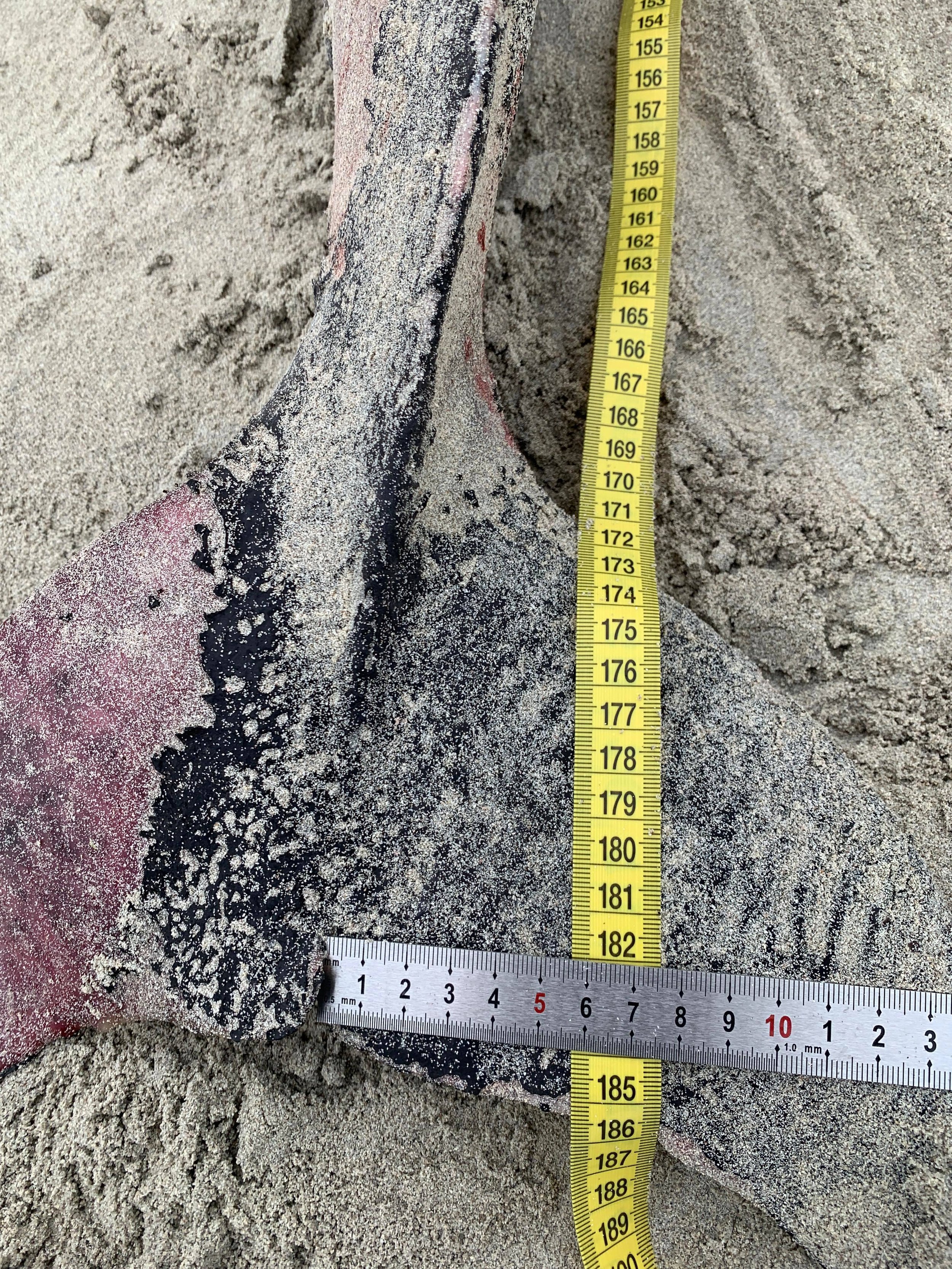

Rake marks indicative of a bottlenose dolphin attack

“SMASS has been in operation since 1992 and is part of the Cetacean Stranding Investigation Programme (CSIP), funded by the Scottish and Westminster Governments. It aims to provide systematic and coordinated approach to the surveillance of Scottish marine species by collating, analysing and reporting data of all whales, dolphins, seal, marine turtles and basking sharks that strand on the Scottish coastline.”

The HWDT team were provided training in taking samples safely from stranded marine animals, including the proper techniques for collecting blubber, skin and tissue samples, along with learning a bit of dentistry by practicing the removal of teeth. A vital part of the process is analysing any injuries present on the body. This is important as it could help shed light on the cause of death. For instance, if there are any rake marks from potential dolphin attacks, entanglement legions or evidence of boat strike.

“Investigation of stranded marine animals can yield substantial information on the health and ecology of these fascinating but often little understood species, while also helping to highlight some of the conservation issues they may face.”

If a carcass is fresh enough and a more thorough investigation is required, then the body will either be collected and sent to SMASS, or the SMASS team will travel to the location of the stranded animal to perform a full necropsy (or post mortem). This enables SMASS to gain a unique insight in the life and death of the animal. Uncovering details such as ‘age structure, sex, body condition, cause of death, pollutant levels, reproductive patterns, diet, disease burden and pathology.’

During the training, we observed this process on a harbour porpoise which had recently washed ashore on the east coast. After doing the initial external assessment - in which a bottlenose dolphin attack was identified as being the likely cause of death - the base samples (blubber, skin, tissue and teeth) were collected, the SMASS team went about opening it up to investigate further.

Broken ribs indicating blunt force trauma from bottlenose dolphin attack

Necropsies, such the one performed by the team on the harbour porpoise, have revealed some stark results; one alarming case study was Lulu, the last recorded female member of the West Coast Community of killer whales. Back in 2016, Lulu stranded on the Isle of Tiree, after becoming entangled in creel rope, subsequent analysis undertaken by SMASS revealed Lulu had a polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) concentration 80 times higher than the accepted PCB toxicity threshold for marine mammals.

Although entanglement or bycatch is one of the most common causes of deaths SMASS has come across, investigation is still needed to determine the full impact of chemical pollution on marine species. Infectious disease also appears to be at the top of many cause of deaths, as was the situation for the Curvier’s beaked whale that live stranded on Mull in 2019.

All this information and the long-term collection of such data, ‘provides a baseline to help detect outbreaks of disease, unusual mortality events, anthropogenic stressors and other health issues, in addition to enabling the assessment of pressures and threats, possible population dynamics and responses to environmental stressors’, all resulting in more understanding of the conservation measures required in order to further protect these enigmatic animals.

A recent documentary ‘What Killed the Whale?’ showcases the substantial effort that goes into collecting this information and the exceptional expertise of the team at SMASS on analysing and retelling in real time the tale of the whale.

Two weeks after completing the SMASS training, Science Officer Hannah Lightley attended her first necropsy. Here she recalls her first callout as a SMASS volunteer:

Having learnt so much from the SMASS training event in Oban, I wasn’t expecting to use my new skills so soon but around two weeks later samples were needed from a stranded juvenile Risso’s dolphin that had been found on the Isle of Iona, an island off the coast of Southwest Mull.

Once letting the SMASS team know I was able to attend and receiving the very important ‘M Number’, I headed down to Finnophort, a two-hour drive from Tobermory, where strong winds calmed enough to make the 10-minute ferry crossing to Iona. A 30min walk from the ferry, past Iona Abbey, and Nunnery, towards the NE coast of the island; a What3Words location led straight to the exact spot of the stranded cetacean at White Strand Of The Monks.

A wee dig was needed to be able to move the body for sampling and pictures. Once moved the cetacean was identified as a juvenile female Risso’s dolphin with no obvious trauma, cuts, marks, or lesions (only some bad sunburn). Measurements of the length and girth of the animal alongside pictures determining sex and body condition were taken before an incision was made to collect samples of blubber, skin, and muscle. Once all info had been collected, samples were packaged and posted back to SMASS for further analysis.

Despite the sadness of the situation, it was great to be able to gather samples and information to understand more about the threats and pressures marine mammals are facing in the Scottish waters as well as speak to onlookers at the beach about HWDT and the SMASS volunteer network.

SMASS has been collecting data on marine animal strandings since 1992, with 2022 marking their 30th year. In that time, they have gathered over 14,000 records from over 2300 cases, with 700 samples collected by their network of volunteers, from a total of 29 species.